As gold and silver continue their steep climb, many precious metals investors no doubt are thinking about what their profit targets are, and when they might exit their positions in this current precious metals bull market cycle and rotate back into stocks and other investments after the crash of the Everything Bubble brings equities and real estate prices back to earth.

Using the last 2007-2009 recession as an example, silver topped first in 2011 followed by gold:

I was planning on using this same playbook for the next upcoming (imminent) recession that will surely precipitate bazooka QE followed by a spectacular run in gold & silver, and then look for signs of a top to sell my gold and silver (and miners) to finance rental property investments when real estate prices bottom out.

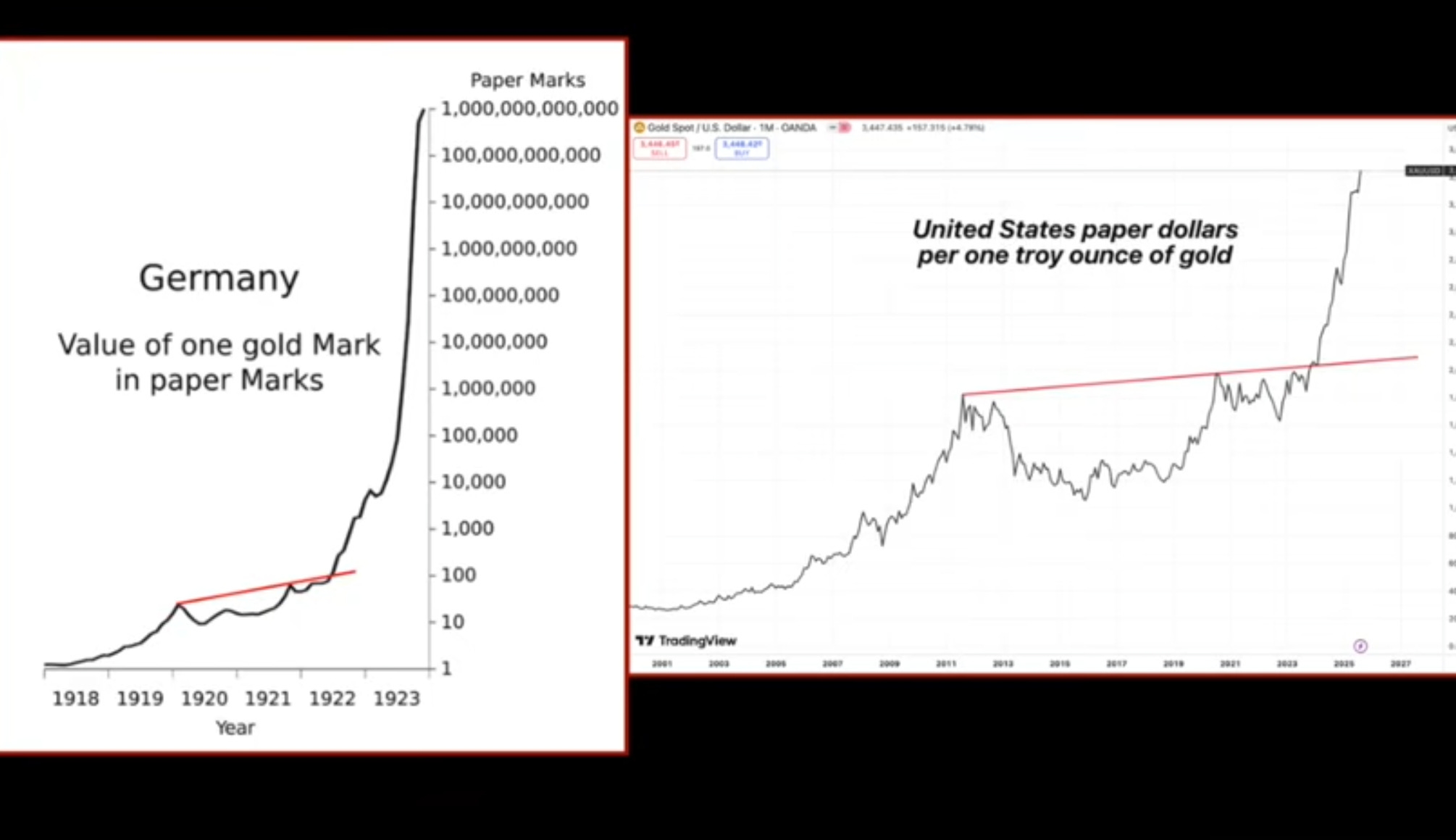

That was the plan… until I saw this comparison of two side-by-side charts below (from The Pareto Investor). This particular coupling of charts caught my eye, and has been nagging at me ever since.

I was intrigued by these side-by-side charts, in particular the neckline the author had drawn across the cup & handle pattern in both, which in my opinion clearly highlights the striking similarity between them.

Just for kicks, because I wanted to more closely examine the similarity between these two charts, I copied and superimposed the Weimar chart on top of a chart from goldprice.org, combining the two as shown below to obtain a more direct visual comparison:

Of course, this is not going to be an apples to apples comparison, as the time frame of the Weimar hyperinflation from 1918-1923 was very compressed compared to what is occurring right now with gold priced in USD. So when I copied the Weimar chart and overlayed it, I had to stretch the X and Y axis a bit to try and obtain the best fit to the Gold/USD chart.

However, I was truly astonished at how closely the initial curved run-up in price to the cup & handle patterns matched (almost identically), and how the peaks of the left and right edge of the cup lined up. The points of confirmation of the neckline breakouts from the cup & handle patterns differed slightly, but after the breakout we all know what happened next in Weimar…

So the question then becomes, are we past the point of no return in Gold/USD? Are we really on the verge of hyperinflation here in the United States? How could it be possible that this could happen to the most powerful country in the world, and so quickly? I had always thought hyperinflation might occur here, but that it was sometime far off in the distant future.

Doing a quick Photoshop comparison by superimposing charts is certainly not a rigorous scientific, mathematical or statistical comparison of Weimar gold prices to today’s gold in USD. However, the similarities between the two charts are clearly apparent upon visual inspection, and I am beginning to wonder if we are reaching the terminal phase for the USD as the pattern above would indicate. Perhaps this time I might rethink my plan for short-term profit taking to finance other investments, and that instead I might hold onto my gold and silver for dear life until the conclusion of this monetary reset we have all been told is coming…whatever that may look like.

. . .

Last weekend I watched a movie called A Night to Remember (1958) about the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. I recommend that all of you watch that movie, not because it has anything to do with investments, but because it is analogous to the situation in which we find ourselves today.

Many financial analysts have drawn comparisons between the anticipated upcoming crash of the Everything Bubble to the Titanic striking an iceberg. In particular, Henrik Zeberg, who is a brilliant technical analyst, has stated that his models indicate we have already hit the iceberg, and it is only a matter of time before we enter recession or worse.

What struck me about this RMS Titanic movie is the portrayal of the psychology of the passengers, even after hitting the iceberg, clinging to their belief that the Titanic was unsinkable. I can remember communicating my worries several years ago about potential hyperinflation to relatives who responded with looks that clearly said “Don’t be ridiculous, that could never happen here!”

Yet here we are, with the Weimar vs Gold/USD chart shown above, and the still shot from the movie showing Thomas Andrews, the architect of the RMS Titanic — examining the damage from the iceberg and explaining to Captain Edward John Smith that the Titanic is going to sink. After coming to terms with the harsh reality of the situation, the captain then orders the lifeboats be swung out and prepared for the women and children.

As I watched the movie, and the final terrifying plunge of the Titanic into the freezing abyss with 1500 people still aboard who tragically lost their lives, I thought about the impending financial crisis and destruction of wealth that is occurring in the form of currency debasement “first slowly, then suddenly all at once”. And my attention then turned to the Weimar chart above, and to the warnings issued by many others who have stated that gold (and silver) are the lifeboats that will save those and their families who had the foresight to recognize this impending global debt catastrophe.

I am very interested to know what other people’s thoughts are regarding where we are on the hyperinflation curve, and whether you believe that we have a couple cycles of ups and downs left to buy and sell… or if you are convinced that we are beyond the point of no return, and that this gold run will only go vertical from here. Please do share your thoughts in the comments below.