** 25-Feb-2022 World View: Germany in World War I

Navigator wrote: Thu Feb 24, 2022 9:41 pm

> I am actually published in multiple areas regarding WW1, having

> researched it extensively. I have written a book and have

> published detailed military simulations and a host of articles on

> the subject.

> WW1 was an "all in" war for Germany. The Kaiser had the complete

> support of the population up until about Jun of 1918, when people

> realized that they no longer had any hope of winning the war.

> The country went through complete mobilization, complete

> conversion to a war economy, and even years of starvation in their

> total support of the Kaiser's misguided war efforts.

> Only at the very end did the navy mutiny (when ordered to commit

> suicide), while the army conducted a fighting retreat until the

> armistice could be negotiated.

I admit to being confused by your description, since it somewhat

contradicts what I've seen in the past. Perhaps the difference is

that you're focusing on the military, while I'm focusing on the mood.

One could say that America's armed forces were "all in" for the

Vietnam War, especially while Lyndon Johnson was president, but there

was also an anti-war sentiment which isn't present in crisis wars.

There was a definite anti-war sentiment in Germany, as described in

Remarque's 1928 novel, Im Westen Nichts Neues (All Quiet on the

Western Front).

http://www.thebellacademy.com/uploads/2 ... l_text.pdf

The anti-war sentiment was bookended by two remarkable events: At the

beginning of the war, the was the famous "Christmas Truce".

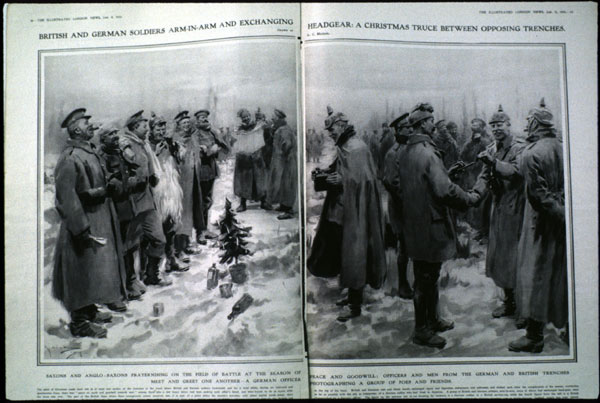

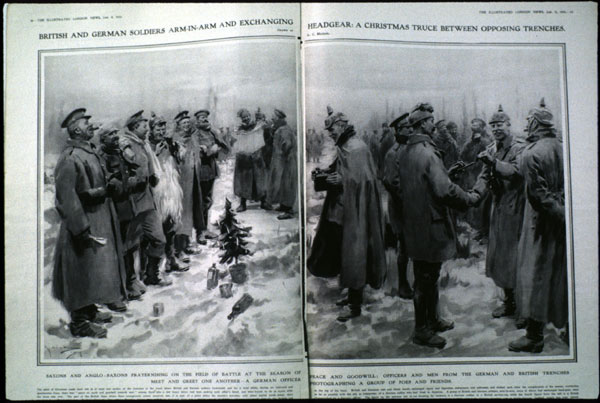

- Christmas truce drawing from the London News of January

9, 1915. The drawing's caption reads, in part, "British and

German soldiers arm-in-arm and exchanging headgear: a Christmas truce

between opposing trenches. Drawn by A. C. Michael.

On December 24, 1914, the German and British soldiers laid down their

arms, crossed into the "No Man's Land" separating their trenches.

They sang Christmas carols, played games, and shared jokes and beer

with one another. Hundreds and perhaps thousands of men on the

Western Front experienced the informal truce. The war had begun only

months earlier, and there was probably more curiosity than hatred

between British and German troops. Once the soldiers began receiving

Christmas presents from home, the mood in many areas became more

festive than warlike.

** 25-Dec-17 World View -- Remembering the 1914 World War I Christmas Truce

** http://www.generationaldynamics.com/pg/ ... tm#e171225

The other bookend was Germany's unexpected capitulation, well before

it was necessary, including the Navy's refusal to obey the Kaiser.

The following is what I wrote in my original Generational Dynamics

book:

**** Why wasn't World War I a Crisis War for Germany?

Germany's amazing capitulation in World War I is only one of the many

indications that World War I wasn't a crisis war for Germany, as it

wasn't for America.

This is one of the most common questions I hear: Aren't you calling

World War II a crisis war, but not World War I, just to make

Generational Dynamics work?

But in fact when you drill down into the actual history of what

happened in America and Germany in WW I, you find that there was so

little motivation on all sides to fight that war, it's a wonder that

The Great War was fought at all.

First, however, the question of whether World War I was a crisis war

is a meaningless question. By the Principle of Localization, it only

makes sense to ask that question for a particular local region or

nation.

There is no question that World War I was a crisis war for Eastern

Europe (while World War II was a crisis war for Western Europe).

- World War I was a crisis war for the Balkans, leading to the

creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1918.

- World War I was a crisis war for Turkey, leading to the

destruction of the Ottoman Empire.

- World War I was a crisis war for Russia, with an internal

revolution in the form of a Bolshevik (Communist) Revolution and a

large violent civil war.

It's worth pointing out, in passing, that all of these wars were

revisited 80 years later, in the 1990s, with the collapse of the

Soviet Union, wars in Bosnia and Kosovo, the civil war in Turkey, and

other regional wars.

World War I did not result in any such dramatic changes in Western

Europe. There was a scapegoating change of government in Germany,

but nothing like the massive structural changes in Russia or Turkey.

In chapter 2, we discussed why World War I was not a crisis war for

America. America remained neutral for many years, despite repeated

German terrorist attacks on Americans, there was a powerful pacifist

(antiwar) movement that included high government officials, and it

resulted in no important transformations in America.

But in fact, World War I was not even a crisis war for

Germany.

First, there's the issue of advance preparation. In Germany's

previous crisis period, the Wars of German Unification (1860-71), as

well as in World War II (1938-45) in the following crisis period,

Germany prepared for war well in advance, and initiated war because of

real animus towards its enemies. But in World War I, Germany did

little advance preparation, and was pulled into the war because of a

long-standing treaty with Austria.

Germany never really pursued the war against France with the

bloodthirsty zeal it did in 1870 and 1939. The war began in 1914,

and was a stalemate for years. During the Christmas season of 1914,

the German high command shipped thousands of Christmas trees to the

front lines, cutting into its ammunition shipments. This led to

a widely publicized Christmas truce between the British and German

troops, where soldiers and officers on both sides all got together and

sang Christmas carols.

To put this kind of event in perspective, shortly after the attacks

of 9/11/2001, American invaded Afghanistan to destroy the al-Qaeda

forces. Can you imagine American soldiers and al-Qaeda forces

getting together on the battlefield in December 2001, to participate

in some holiday festivities?

It's this very difference in attitude and intensity that

distinguishes mid-cycle wars from crisis wars.

In fact, this lack of intensity characterizes Germany's entire

campaign.

In August 1914, Germany planned a quick, total victory over France,

requiring only six weeks -- too quick for the British troops to be

deployed to stop the advance into France. The plan went

fantastically well for about two weeks -- but then the Germans sent

two corps of soldiers to the eastern front to fight the Russians.

Without those soldiers, Germany's rapid sweep was halted by the French

long enough to give the British troops time to reinforce the French.

Both the German and French sides dug themselves into static trenches.

It was from those positions that the Christmas truce took place. The

stalemate continued with millions of each side's troops killed in

battle, until 1917, when America entered the war.

Much has been written about the defeat of Germany once America

entered the war, but little about the extraordinary circumstances of

that defeat.

When France capitulated to Germany in the Franco-Prussian war of

1870, Germany was deep into French territory. In 1945, Hitler

committed suicide when the Allies were practically in Berlin. In

crisis wars, when the people of a country believe that their very

existence is at stake, capitulation does not come easily.

But when Germany capitulated on November 11, 1918, German troops were

still deep within Belgian and French territory. Writing in 1931,

Winston Churchill said that if Germany had continued to fight, they

would have been capable of inflicting two million more casualties upon

the enemy. Churchill added that the Allies would not have put Germany

to the test: simply by fighting on a little longer, the Allies would

have negotiated a peace with no reparations, on terms far more

favorable to Germany than actually occurred in the peace dictated by

the Allies.

Actually, the seeds of capitulation had been planted three months

earlier, on August 8, when the German high command realized that too

much time had passed, and the absolute military triumph over France

could no longer be achieved. From that time, the Germans lost most of

whatever remaining spirit they had, and completely lost momentum. They

called for cease-fire on October 4, expecting the German army and

people to rise up and demand victory, and planning to launch a new

attack with replenished strength, once the cease-fire had expired.

However, the mood in Germany turned firmly against renewing

hostilities, in both the army and the people. By the end of October,

it was apparent to the high command that it was too late. Writing

after the war, Prince Max von Baden of the high command concluded,

"The masses would likely have risen, but not against the

enemy. Instead, they would have attacked the war itself and the

'military oppressors' and 'monarchic aristocrats,' on whose behalf, in

their opinion, it had been waged."

I've written about these events at length to illustrate the

difference between mid-cycle wars and crisis wars. Try to imagine

Hitler losing momentum in this way in World War II, or imagine

Britain, America or Japan losing momentum and capitulating

unnecessarily in World War II. It's almost impossible to imagine it,

since World War II was a crisis war, while World War I was not.

Indeed, there's only one major war in the lifetime of most readers

where events proceeded in any way similarly to the actions of the

Germans in World War I: the actions of America in Vietnam in the

1970s.

America was forced repeatedly by its own antiwar movement to accept

various Christmas truces during the Vietnam War; the Vietnamese never

honored such truces, since that was a crisis war for them and a

mid-cycle war for us. American soldiers were court-martialed because

of the unnecessary killing of civilians during the Vietnam War, and

yet America purposely killed civilians in World War II by carpet

bombing Dresden, and by nuclear attacks on Japan. Finally, America

withdrew from Vietnam and capitulated, when it clearly had the power

to win that war if it had wanted to.