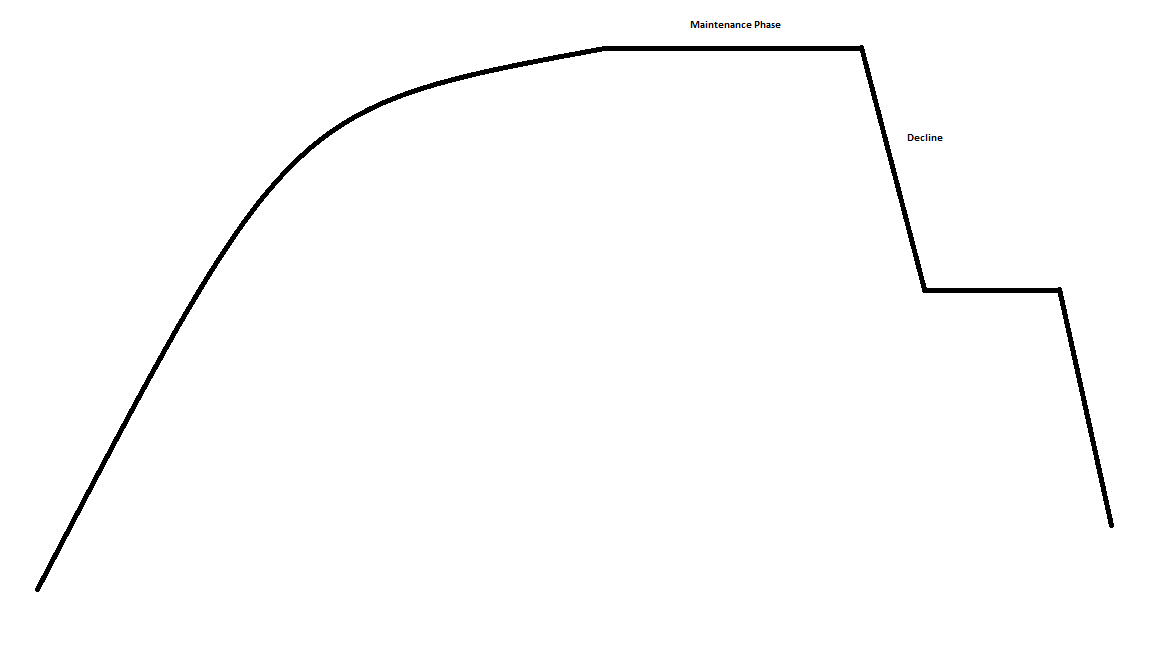

The Archdruid wrote:It’s when decline sets in and maintaining the existing level of complexity becomes a problem that the trouble begins. Under some conditions, intermediation can benefit the productive economy, but in a complex economy, more and more of the intermediation over time amounts to finding ways to game the system, profiting off economic activity without actually providing any benefit to anyone else. A complex society at or after its zenith thus typically ends up with a huge burden of unproductive economic activity supported by an increasingly fragile foundation of productive activity.

All the intermediaries, the parasitic as well as the productive, expect to be maintained in the style to which they’re accustomed, and since they typically have more wealth and influence than the producers and consumers who support them, they can usually stop moves to block their access to the feed trough. Economic contraction, however, makes it hard to support business as usual on the shrinking supply of real wealth. The intermediaries thus end up competing with the actual producers and consumers of goods and services, and since the intermediaries typically have the support of governments and institutional forms, more often than not it’s the intermediaries who win that competition.

It’s not at all hard to see that process at work; all it takes is a stroll down the main street of the old red brick mill town where I live, or any of thousands of other towns and cities in today’s America. Here in Cumberland, there are empty storefronts all through downtown, and empty buildings well suited to any other kind of economic activity you care to name there and elsewhere in town. There are plenty of people who want to work, wage and benefit expectations are modest, and there are plenty of goods and services that people would buy if they had the chance. Yet the storefronts stay empty, the workers stay unemployed, the goods and services remain unavailable. Why?

The reason is intermediation. Start a business in this town, or anywhere else in America, and the intermediaries all come running to line up in front of you with their hands out. Local, state, and federal bureaucrats all want their cut; so do the bankers, the landlords, the construction firms, and so on down the long list of businesses that feed on other businesses, and can’t be dispensed with because this or that law or regulation requires them to be paid their share. The resulting burden is far too large for most businesses to meet. Thus businesses don’t get started, and those that do start up generally go under in short order. It’s the same problem faced by every parasite that becomes too successful: it kills the host on which its own survival depends.

That’s the usual outcome when a heavily intermediated market economy slams face first into the hard realities of decline. Theoretically, it would be possible to respond to the resulting crisis by forcing disintermediation, and thus salvaging the market economy. Practically, that’s usually not an option, because the disintermediation requires dragging a great many influential economic and political sectors away from their accustomed feeding trough. Far more often than not, declining societies with heavily intermediated market economies respond to the crisis just described by trying to force the buyers and sellers of goods and services to participate in the market even at the cost of their own economic survival, so that some semblance of business as usual can proceed.

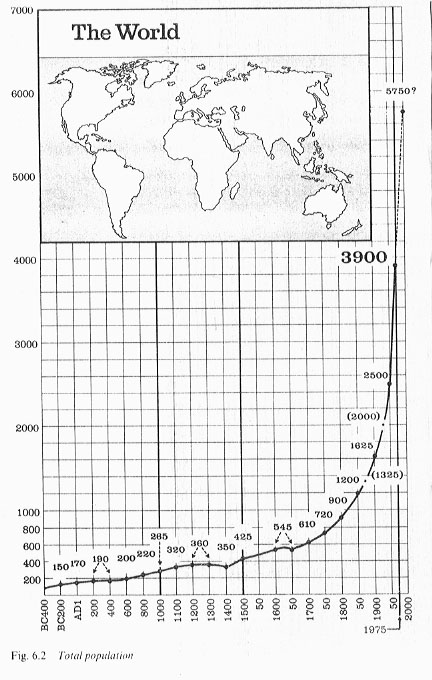

That’s why the late Roman Empire, for example, passed laws requiring that each male Roman citizen take up the same profession as his father, whether he could survive that way or not. That’s also why, as noted last week, so many American jurisdictions are cracking down on people who try to buy and sell food, medical care, and the like outside the corporate economy. In the Roman case, the attempt to keep the market economy fully intermediated ended up killing the market economy altogether, and in most of the post-Roman world—interestingly, this was as true across much of the Byzantine empire as it was in the barbarian west—the complex money-mediated market economy of the old Roman world went away, and centuries passed before anything of the kind reappeared.

What replaced it is what always replaces the complex economic systems of fallen civilizations: a system that systematically chucks the intermediaries out of economic activity and replaces them with personal commitments set up to block any attempt to game the system: that is to say, feudalism.

There’s enough confusion around that last word these days that a concrete example is probably needed here. I’ll borrow a minor character from a favorite book of my childhood, therefore, and introduce you to Higg son of Snell. His name could just as well be Michio, Chung-Wan, Devadatta, Hafiz, Diocles, Bel-Nasir-Apal, or Mentu-hetep, because the feudalisms that evolve in the wake of societal collapse are remarkably similar around the world and throughout time, but we’ll stick with Higg for now. On the off chance that the name hasn’t clued you in, Higg is a peasant—a free peasant, he’ll tell you with some pride, and not a mere serf; his father died a little while back of what people call “elf-stroke” in his time and we’ve shortened to “stroke” in ours, and he’s come in the best of his two woolen tunics to the court of the local baron to take part in the ceremony at the heart of the feudal system.

It’s a verbal contract performed in the presence of witnesses: in this case, the baron, the village priest, a couple of elderly knights who serve the baron as advisers, and a gaggle of village elders who remember every detail of the local customary law with the verbal exactness common to learned people among the illiterate. Higg places his hands between the baron’s and repeats the traditional pledge of loyalty, coached as needed by the priest; the baron replies in equally formal words, and the two of them are bound for life in the relationship of liegeman to liege lord.

What this means in practice is anything but vague. As the baron’s man, Higg has the lifelong right to dwell in his father’s house and make use of the garden and pigpen; to farm a certain specified portion of the village farmland; to pasture one milch cow and its calf, one ox, and twelve sheep on the village commons; to gather, on fourteen specified saint’s days, as much wood as he can carry on his back in a single trip from the forest north of the village, but only limbwood and fallen wood; to catch two dozen adult rabbits from the warren on the near side of the stream, being strictly forbidden to catch any from the warren on the far side of the millpond; and, as a reward for a service his great-grandfather once performed for the baron’s great-grandfather during a boar hunt, to take anything that washes up on the weir across the stream between the first sound of the matin bell and the last of the vespers bell on the day of St. Ethelfrith each year.

In exchange for these benefits, Higg is bound to an equally specific set of duties. He will labor in the baron’s fields, as well as his own and his neighbors, at seedtime and harvest; his son will help tend the baron’s cattle and sheep along with the rest of the village herd; he will give a tenth of his crop at harvest each year for the support of the village church; he will provide the baron with unpaid labor in the fields or on the great stone keep rising next to the old manorial hall for three weeks each year; if the baron goes to war, whether he’s staging a raid on the next barony over or answering the summons of that half-mythical being, the king, in the distant town of London, Higg will put on a leather jerkin and an old iron helmet, take a stout knife and the billhook he normally uses to harvest wood on those fourteen saint’s days, and follow the baron in the field for up to forty days. None of these benefits and duties are negotiable; all Higg’s paternal ancestors have held their land on these terms since time out of mind; each of his neighbors holds some equivalent set of feudal rights from the baron for some similar set of duties.

Higg has heard of markets. One is held annually every St. Audrey’s day at the king’s town of Norbury, twenty-seven miles away, but he’s never been there and may well never travel that far from home in his life. He also knows about money, and has even seen a silver penny once, but he will live out his entire life without ever buying or selling something for money, or engaging in any economic transaction governed by the law of supply and demand. Not until centuries later, when the feudal economy begins to break down and intermediaries once again begin to insert themselves between producer and consumer, will that change—and that’s precisely the point, because feudal economics is what emerges in a society that has learned about the dangers of intermediation the hard way and sets out to build an economy where that doesn’t happen.

This Dark Age America series from The Archdruid, written in late 2014, shows him in top form, in my opinion.