A more attractive model is emerging: The company funds or co-funds PhD candidates or postdoctoral researchers studying difficult scientific problems or new areas of technology of interest to the company, and its scientists or engineers co-mentor the researchers with faculty members. If something promising emerges, then more funding is forthcoming either directly from the company or via a collaborative proposal to a government agency by the university and the company.

For example, my school has recently partnered with Schlumberger to co-fund PhD students on projects, some of which have justified continued funding from the company.

Companies also recognize that top talent is not confined to just a handful of schools. The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education identifies 107 colleges and universities as engaging in the “highest research activity.” Companies are tapping into the rich resources they offer.

For instance, a little over five years ago Procter & Gamble funded a Modeling and Simulation Center for Product Development at the University of Cincinnati that focuses on collaborative research projects and the co-mentoring of PhD students. And in 2015 the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and pharma giant GlaxoSmithKline announced the creation of a dedicated HIV Cure center and a jointly owned new company that will focus on discovering a cure for HIV/AIDS. A small research team from GSK moved to Chapel Hill to be co-located with UNC researchers.

https://hbr.org/2018/01/why-companies-a ... aborations

The purpose of my previous post was to illustrate that this model has been in place without the co-mentoring add-on for at least 40 years. It is nothing new. Harvard Business Review has to know this. It's very, very difficult for me to imagine that they don't.

The previous post was not to say that I understand the details of how researchers were solving (or approximating solutions to) partial differential equations for big oil because I never got involved in it. However, at that time, I felt that I was being targeted as a dupe and that agreeing to pursue a PhD in that manner was almost equivalent to being a slave on an industrial plantation. I saw professors who were making excuses to keep graduate students there for 6 years. During that time, my mother clipped and mailed a newspaper article describing how a student at a different institution shot and killed a professor for interminably keeping him in a PhD program and not letting him go.

Fortunately, at that time there were still alternatives. I found the lowest tier of school in the cheapest location that would fund me for the largest amount (it was $10,000 per year tax free in 1983), hung out for a few months pretending I somehow got in the wrong place, dumbed myself down and found a job through informal channels, as described previously. While I was there waiting to get employed, I lived in a big rooming house, played chess and watched TV with the kids I was living with, worked out at the university gym, went to video arcades, picked up used books, and was still able to pass my classes, all on big oil's dime.

However, what I suspect is that with the new Dark Age tightening its grip, corporate America and the universities would like to figure out a way to delay lots more young people from reaching the age at which they find gainful employment, while still reaping all the benefits. It could become almost a rite of passage to "collaborate" with PhD candidates while paying them puny stipends and corralling them on industrial plantations for several years instead of paying them living wages. As the article states, "Companies also recognize that top talent is not confined to just a handful of schools. The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education identifies 107 colleges and universities as engaging in the “highest research activity.”" What a convenient revelation!

Almost ten years ago, the typical progression I was seeing for young people where I was working was a bachelor's degree, a master's degree, a couple years doing various low paid work (even including things like waitressing) while living at home, employment as a contractor for about a year where I was working and, if they were lucky(?) and didn't get fired, placement into a full time entry level job with benefits at age 25 to 27. None of the delay between bachelor's and first entry level job was necessary. I felt it was the system's way to hold on. But it can't hold on forever by delaying the birth of the first child for this cohort to later and later ages, with fewer children also.

Both industry and academia stand to benefit from long-term cooperation. Companies will gain greater access to cutting-edge research and scientific talent at a time when corporate R&D budgets are increasingly under pressure. Universities will gain access to financial support and partners in research at a time when government funding is shrinking.

While students get a piece of paper.

That's moving in the wrong direction.

Higgenbotham wrote: Fri Dec 02, 2022 5:23 pm

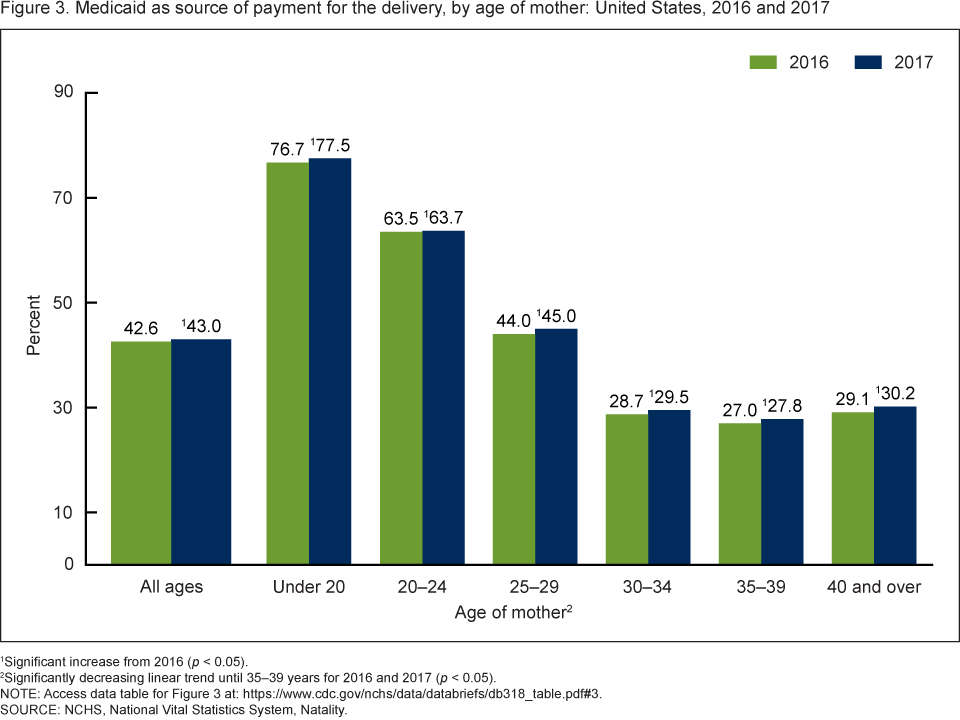

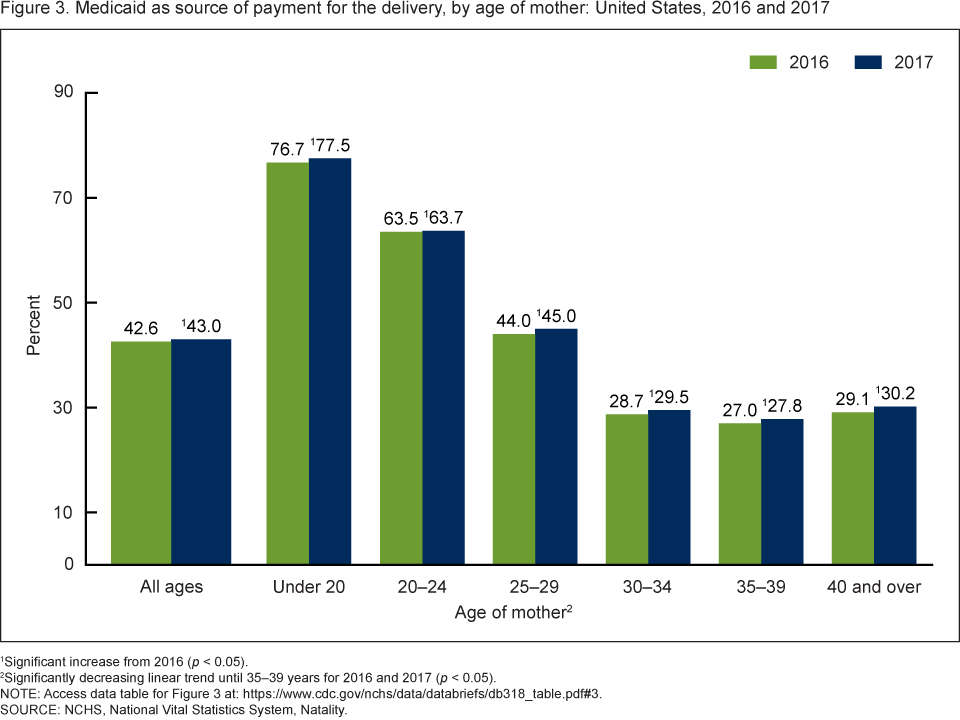

The key point in the repeat of the data below is: "These two sets of data show that there is virtually nobody with any financial means under the age of 25 giving birth in America today." Eyeballing the data below, it can be calculated that about 8 percent of the births in the United States are to women under age 25 who are not on Medicaid. That's a pretty sobering statistic. It corroborates the fact that there are virtually no jobs in the United States available to support young families.

Higgenbotham wrote: Wed Jun 05, 2019 1:56 am

Results—The provisional number of births for the United States in 2018 was 3,788,235, down 2% from 2017 and the lowest number of births in 32 years. The general fertility rate was 59.0 births per 1,000 women aged 15–44, down 2% from 2017 and another record low for the United States. The total fertility rate declined 2% to 1,728.0 births per 1,000 women in 2018, another record low for the nation. Birth rates declined for nearly all age groups of women under 35, but rose for women in their late 30s and early 40s.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-007-508.pdf

Higgenbotham wrote: Fri May 21, 2021 11:08 am

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/nata ... hboard.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/nata ... hboard.htm

Selecting "Age Specific Birth Rates" on the left gives this chart.

I've posted the below graph before. These two sets of data show that there is virtually nobody with any financial means under the age of 25 giving birth in America today.

Higgenbotham wrote: Sat Dec 03, 2022 11:30 am

Higgenbotham wrote: Fri Dec 02, 2022 5:23 pm

Eyeballing the data below, it can be calculated that about 8 percent of the births in the United States are to women under age 25 who are not on Medicaid.

I went to the CDC site and got the numbers for the data shown. Since the data is based on rate (number of births per thousand), this calculation assumes that the population in each 5 year cohort is the same. The ages of the cohorts are followed by the rate.

30-34 94.9

25-29 90.2

20-24 63.0

35-39 51.8

15-19 15.4

40-44 11.8

All the rates sum to 327.1.

The percentage of births not on Medicaid who are under age 25 is therefore about:

[15.4*(1 - 0.775) + 63.0*(1 - 0.637)]/327.1 x 100 = 8.0%.

Having the majority of births to women aged 25-34, while mostly OK on an individual basis, is probably not OK for the population at large, or at least not as good as the majority of births being to women aged 18-24, who on average are going to be healthier. Most of these births to women aged 25-34 would also be to fathers who are older than the women. At these ages, genetic defects, while still small on an individual basis, are probably increasing enough to have a negative effect on the health of the population, especially if this were to continue for several generations. I am no expert on these matters, but I am also skeptical that there are any true experts, as is the case with many health issues today.

American families changed a lot starting in the 1960s and 1970s. Two years stand out in particular: 1960, when the birth-control pill entered the market, and 1973, when the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade. A new study makes the provocative argument that the latter, not the former, is what really prompted Americans to get married and start having children at older ages than they used to. (Hat tip to Tyler Cowen; free draft of the paper here.)

https://nationalreview.com/corner/how-s ... -unfolded/

If this is true (and I'm skeptical about this too), this effect of abortion on the health of the future population did us no favors.