Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

Unrelated factors that we don't have time to go into here.

https://www.theinteldrop.org/2023/06/11 ... scaneagle/

https://www.theinteldrop.org/2023/06/11 ... scaneagle/

Last edited by aeden on Mon Jun 12, 2023 6:25 am, edited 1 time in total.

-

guest

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

Let me just say what’s on everyone’s mind. They got rid of the white people that brought civilisation to South Africa and Rhodesia.

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

The Archdruid wrote: Sun Jun 11, 2023 3:29 pm Imagine for a moment that one of the current US elite—an executive from a too-big-to-fail investment bank, a top bureaucrat from inside the DC beltway, a trust-fund multimillionaire with a pro forma job at the family corporation, or what have you—were to turn up in some chaotic failed state on the fringes of the industrial world, with no money, no resources, no help from abroad, and no ticket home. What’s the likelihood that, without anything other than whatever courage, charisma, and bare-knuckle fighting skills he might happen to have, some such person could equal Odoacer’s feat, win the loyalty and obedience of thousands of gang members and unemployed mercenaries, and lead them in a successful invasion of a neighboring country?

There are people in North America who could probably carry off a feat of that kind, but you won’t find them in the current ruling elite. That in itself defines part of the path to dark age America: the replacement of a ruling class that specializes in managing abstract power through institutions with a ruling class that specializes in expressing power up close and in person, using the business end of the nearest available weapon. The process by which the new elite emerges and elbows its predecessors out of the way, in turn, is among the most reliable dimensions of decline and fall; we’ll talk about it next week.

https://thearchdruidreport-archive.2006 ... index.html

Higgenbotham wrote: Wed Jan 16, 2019 9:01 pm Always remember that the world runs at approximately the 97th percentile (in terms of ability).

Yes, the smartest people on average are at the centers of power. But just on average.

The absolute ablest individuals always exist on the periphery. Attila the Hun for example. Some of these individuals will rise to the top when the center collapses and the bailouts are no longer possible.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

aeden wrote: Sun Jun 11, 2023 4:33 pm Sun Jul 01, 2012 9:29 pm

A guy wants to increase existing production. Thugs want 120k impact study to what he already does.

Evil and plain economic murder.

https://thearchdruidreport-archive.2006 ... onomy.htmlThe Archdruid wrote:It’s when decline sets in and maintaining the existing level of complexity becomes a problem that the trouble begins. Under some conditions, intermediation can benefit the productive economy, but in a complex economy, more and more of the intermediation over time amounts to finding ways to game the system, profiting off economic activity without actually providing any benefit to anyone else. A complex society at or after its zenith thus typically ends up with a huge burden of unproductive economic activity supported by an increasingly fragile foundation of productive activity.

All the intermediaries, the parasitic as well as the productive, expect to be maintained in the style to which they’re accustomed, and since they typically have more wealth and influence than the producers and consumers who support them, they can usually stop moves to block their access to the feed trough. Economic contraction, however, makes it hard to support business as usual on the shrinking supply of real wealth. The intermediaries thus end up competing with the actual producers and consumers of goods and services, and since the intermediaries typically have the support of governments and institutional forms, more often than not it’s the intermediaries who win that competition.

It’s not at all hard to see that process at work; all it takes is a stroll down the main street of the old red brick mill town where I live, or any of thousands of other towns and cities in today’s America. Here in Cumberland, there are empty storefronts all through downtown, and empty buildings well suited to any other kind of economic activity you care to name there and elsewhere in town. There are plenty of people who want to work, wage and benefit expectations are modest, and there are plenty of goods and services that people would buy if they had the chance. Yet the storefronts stay empty, the workers stay unemployed, the goods and services remain unavailable. Why?

The reason is intermediation. Start a business in this town, or anywhere else in America, and the intermediaries all come running to line up in front of you with their hands out. Local, state, and federal bureaucrats all want their cut; so do the bankers, the landlords, the construction firms, and so on down the long list of businesses that feed on other businesses, and can’t be dispensed with because this or that law or regulation requires them to be paid their share. The resulting burden is far too large for most businesses to meet. Thus businesses don’t get started, and those that do start up generally go under in short order. It’s the same problem faced by every parasite that becomes too successful: it kills the host on which its own survival depends.

That’s the usual outcome when a heavily intermediated market economy slams face first into the hard realities of decline. Theoretically, it would be possible to respond to the resulting crisis by forcing disintermediation, and thus salvaging the market economy. Practically, that’s usually not an option, because the disintermediation requires dragging a great many influential economic and political sectors away from their accustomed feeding trough. Far more often than not, declining societies with heavily intermediated market economies respond to the crisis just described by trying to force the buyers and sellers of goods and services to participate in the market even at the cost of their own economic survival, so that some semblance of business as usual can proceed.

That’s why the late Roman Empire, for example, passed laws requiring that each male Roman citizen take up the same profession as his father, whether he could survive that way or not. That’s also why, as noted last week, so many American jurisdictions are cracking down on people who try to buy and sell food, medical care, and the like outside the corporate economy. In the Roman case, the attempt to keep the market economy fully intermediated ended up killing the market economy altogether, and in most of the post-Roman world—interestingly, this was as true across much of the Byzantine empire as it was in the barbarian west—the complex money-mediated market economy of the old Roman world went away, and centuries passed before anything of the kind reappeared.

What replaced it is what always replaces the complex economic systems of fallen civilizations: a system that systematically chucks the intermediaries out of economic activity and replaces them with personal commitments set up to block any attempt to game the system: that is to say, feudalism.

There’s enough confusion around that last word these days that a concrete example is probably needed here. I’ll borrow a minor character from a favorite book of my childhood, therefore, and introduce you to Higg son of Snell. His name could just as well be Michio, Chung-Wan, Devadatta, Hafiz, Diocles, Bel-Nasir-Apal, or Mentu-hetep, because the feudalisms that evolve in the wake of societal collapse are remarkably similar around the world and throughout time, but we’ll stick with Higg for now. On the off chance that the name hasn’t clued you in, Higg is a peasant—a free peasant, he’ll tell you with some pride, and not a mere serf; his father died a little while back of what people call “elf-stroke” in his time and we’ve shortened to “stroke” in ours, and he’s come in the best of his two woolen tunics to the court of the local baron to take part in the ceremony at the heart of the feudal system.

It’s a verbal contract performed in the presence of witnesses: in this case, the baron, the village priest, a couple of elderly knights who serve the baron as advisers, and a gaggle of village elders who remember every detail of the local customary law with the verbal exactness common to learned people among the illiterate. Higg places his hands between the baron’s and repeats the traditional pledge of loyalty, coached as needed by the priest; the baron replies in equally formal words, and the two of them are bound for life in the relationship of liegeman to liege lord.

What this means in practice is anything but vague. As the baron’s man, Higg has the lifelong right to dwell in his father’s house and make use of the garden and pigpen; to farm a certain specified portion of the village farmland; to pasture one milch cow and its calf, one ox, and twelve sheep on the village commons; to gather, on fourteen specified saint’s days, as much wood as he can carry on his back in a single trip from the forest north of the village, but only limbwood and fallen wood; to catch two dozen adult rabbits from the warren on the near side of the stream, being strictly forbidden to catch any from the warren on the far side of the millpond; and, as a reward for a service his great-grandfather once performed for the baron’s great-grandfather during a boar hunt, to take anything that washes up on the weir across the stream between the first sound of the matin bell and the last of the vespers bell on the day of St. Ethelfrith each year.

In exchange for these benefits, Higg is bound to an equally specific set of duties. He will labor in the baron’s fields, as well as his own and his neighbors, at seedtime and harvest; his son will help tend the baron’s cattle and sheep along with the rest of the village herd; he will give a tenth of his crop at harvest each year for the support of the village church; he will provide the baron with unpaid labor in the fields or on the great stone keep rising next to the old manorial hall for three weeks each year; if the baron goes to war, whether he’s staging a raid on the next barony over or answering the summons of that half-mythical being, the king, in the distant town of London, Higg will put on a leather jerkin and an old iron helmet, take a stout knife and the billhook he normally uses to harvest wood on those fourteen saint’s days, and follow the baron in the field for up to forty days. None of these benefits and duties are negotiable; all Higg’s paternal ancestors have held their land on these terms since time out of mind; each of his neighbors holds some equivalent set of feudal rights from the baron for some similar set of duties.

Higg has heard of markets. One is held annually every St. Audrey’s day at the king’s town of Norbury, twenty-seven miles away, but he’s never been there and may well never travel that far from home in his life. He also knows about money, and has even seen a silver penny once, but he will live out his entire life without ever buying or selling something for money, or engaging in any economic transaction governed by the law of supply and demand. Not until centuries later, when the feudal economy begins to break down and intermediaries once again begin to insert themselves between producer and consumer, will that change—and that’s precisely the point, because feudal economics is what emerges in a society that has learned about the dangers of intermediation the hard way and sets out to build an economy where that doesn’t happen.

This Dark Age America series from The Archdruid, written in late 2014, shows him in top form, in my opinion.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

This thing The Archdruid calls intermediation is part of what I call the cost structure and partly what is meant when it's said in these posts that the cost structure is too high - there is too much intermediation.

PS Prior to quoting it from this source, search shows that aeden is the only poster who has used this term in the forum.

PS Prior to quoting it from this source, search shows that aeden is the only poster who has used this term in the forum.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

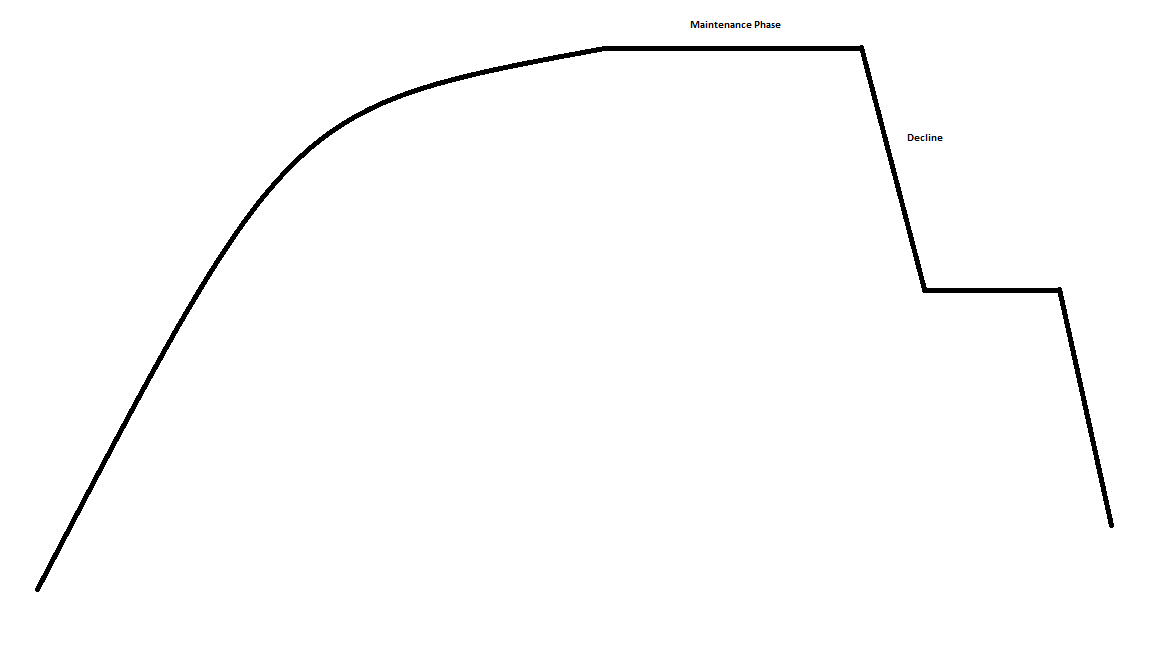

When I say we're near the end of the maintenance phase and close to the decline, in my mind, it looks about like this, which represents a high level of current complexity which will soon ratchet down to lower levels of complexity. I suppose the horizontal line could be pointing downward a bit.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

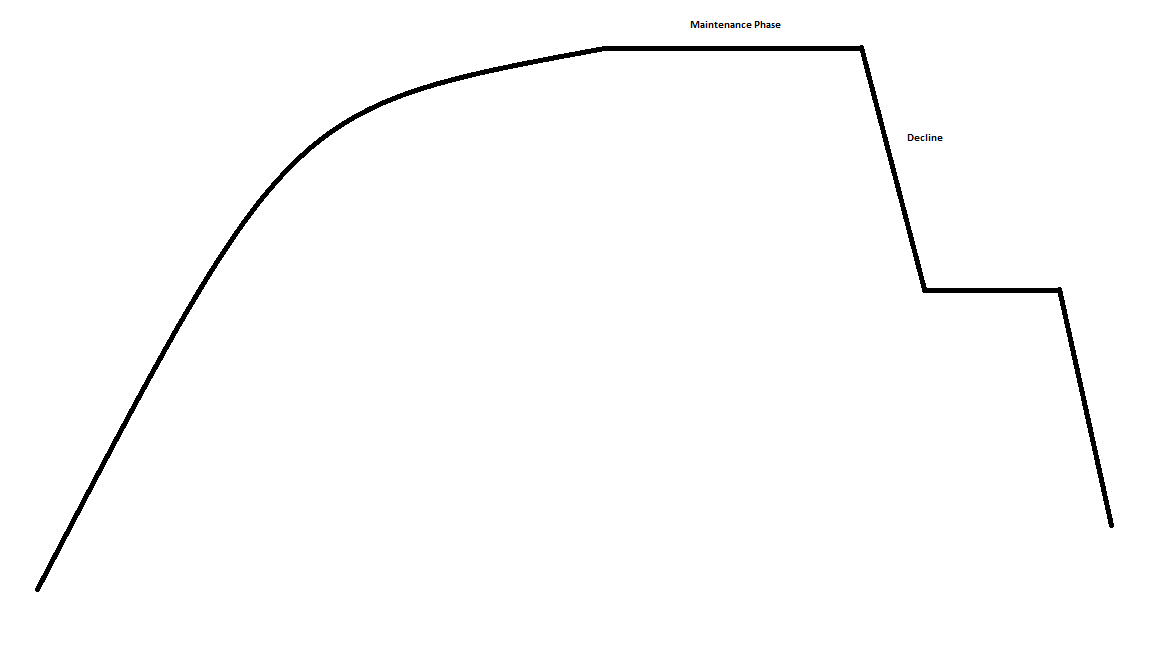

What the maintenance phase looks like.

Higgenbotham wrote: Sat Mar 31, 2018 3:14 pm A few years ago we discussed the AP reports, which primarily focused on the NRC and "pencil engineering". The concept prevalent today is for Boomer managers to have "plausible deniability" as less money is allocated and available for infrastructure and engineers are designated to be blamed when something like the Flint water crisis occurs. After that, the old Soviet playbook comes out and there are Promparty style show trials in the media and the "industrial wreckers" are carted off to prison to do their "tenner".

Part of that process is to place Gen X front line and department managers between the "designated felons" and the Boomer managers who are not licensed engineers and, in many cases, don't even have engineering degrees at all. That helps to insulate the top Boomer managers, who then have more excuses to say they were not properly informed.

Higgenbotham wrote: Mon Aug 25, 2014 9:02 pmPerfect description of what infrastructure engineers do nowadays.Unprompted, several nuclear engineers and former regulators used nearly identical terminology to describe how industry and government research has frequently justified loosening safety standards to keep aging reactors within operating rules. They call the approach "sharpening the pencil" or "pencil engineering" — the fudging of calculations and assumptions to yield answers that enable plants with deteriorating conditions to remain in compliance.

Now that the corrupt elites have a lock on the system, what "increased accountability" means for the individual infrastructure engineer is, "You had better find creative ways to say this rickety crap that can kill people is in compliance or else."

Higgenbotham wrote: Mon Aug 25, 2014 8:46 pm http://www.ap.org/company/awards/part-i-aging-nukes

It was this one. Though I can't find "pencil engineering" in our archives, I'm almost sure you posted this link.

PART I: AP IMPACT: US nuke regulators weaken safety rules

By JEFF DONN

LACEY TOWNSHIP, N.J. (AP) — Federal regulators have been working closely with the nuclear power industry to keep the nation's aging reactors operating within safety standards by repeatedly weakening those standards, or simply failing to enforce them, an investigation by The Associated Press has found.

Time after time, officials at the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission have decided that original regulations were too strict, arguing that safety margins could be eased without peril, according to records and interviews.

The result? Rising fears that these accommodations by the NRC are significantly undermining safety — and inching the reactors closer to an accident that could harm the public and jeopardize the future of nuclear power in the United States.Other notifications lack detail, but aging also was a probable factor in 113 additional alerts. That would constitute up to 62 percent in all. For example, the 39-year-old Palisades reactor in Michigan shut Jan. 22 when an electrical cable failed, a fuse blew, and a valve stuck shut, expelling steam with low levels of radioactive tritium into the air outside.

Higgenbotham wrote: Mon Aug 25, 2014 8:41 pm It occurred to me today that "a" had posted a link some time ago that perfectly describes what the engineering profession has become as it relates to infrastructure, as I had discussed this past weekend. It was the link that described what has become known as "pencil engineering" in the nuclear power industry. In my own words, "pencil engineering" is the use of nonsense justification for relaxing the original standards the NRC put into place for the maintenance and replacement of equipment in the nuclear power industry. It has purely short term profit in mind at the expense of safety to benefit corrupt elites.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

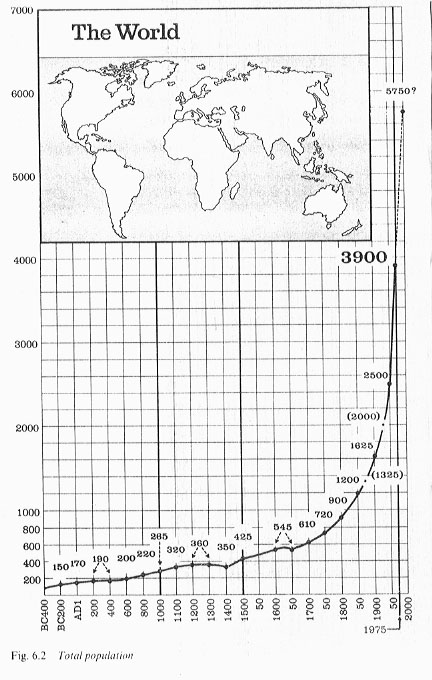

Another view of where we are. I believe Barbara Tuchman had a similar view. There was a poster on this forum early on (approximately 2008 or 2009) who stated this view also.

https://thearchdruidreport-archive.2006 ... fairy.htmlThe historian Arnold Toynbee, whose study of the rise and fall of civilizations is the most detailed and cogent for our purpose, has traced a recurring rhythm in this process. Falling civilizations oscillate between periods of intense crisis and periods of relative calm, each such period lasting anywhere from a few decades to a century or more—the pace is set by the speed of the underlying decline, which varies somewhat from case to case. Most civilizations, he found, go through three and a half cycles of crisis and stabilization—the half being, of course, the final crisis from which there is no recovery.

That’s basically the model that I’m applying to our future. One wrinkle many people miss is that we’re not waiting for the first of the three and a half rounds of crisis and recovery to hit; we’re waiting for the second. The first began in 1914 and ended around 1954, driven by the downfall of the British Empire and the collapse of European domination of the globe. During the forty years between Sarajevo and Dien Bien Phu, the industrial world was hammered by the First World War, the Spanish Flu pandemic, the Great Depression, millions of political murders by the Nazi and Soviet governments, the Second World War, and the overthrow of European colonial empires around the planet.

That was the first era of crisis in the decline and fall of industrial civilization. The period from 1945 to the present was the first interval of stability and recovery, made more prosperous and expansive than most examples of the species by the breakneck exploitation of petroleum and other fossil fuels, and a corresponding boom in technology. At this point, as fossil fuel reserves deplete, the planet’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide and other pollutants runs up against hard limits, and a galaxy of other measures of impending crisis move toward the red line, it’s likely that the next round of crisis is not far off.

What will actually trigger that next round, though, is anyone’s guess. In the years leading up to 1914, plenty of people sensed that an explosion was coming, some guessed that a general European war would set it off, but nobody knew that the trigger would be the assassination of an Austrian archduke on the streets of Sarajevo. The Russian Revolution, the March on Rome, the crash of ‘29, Stalin, Hitler, Pearl Harbor, Auschwitz, Hiroshima? No one saw those coming, and only a few people even guessed that something resembling one or another of these things might be in the offing.

Thus trying to foresee the future of industrial society in detail is an impossible task. Sketching out the sort of future that we could get is considerably less challenging. History has plenty to say about the things that happen when a civilization begins its long descent into chaos and barbarism, and it’s not too difficult to generalize from that evidence.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/fin ... our-wealth

Risk is not probability. Abuse is the risk allowed to covet funds.

https://bombthrower.com/when-whiteboard ... h-reality/

Risk is not probability. Abuse is the risk allowed to covet funds.

https://bombthrower.com/when-whiteboard ... h-reality/

-

Higgenbotham

- Posts: 8123

- Joined: Wed Sep 24, 2008 11:28 pm

Re: Higgenbotham's Dark Age Hovel

This was discussed here at one time. I disagree that the dark age started in 1914, but it's certainly a view that many have, and justifiably so.Higgenbotham wrote: Mon Jun 12, 2023 10:46 am Another view of where we are. I believe Barbara Tuchman had a similar view. There was a poster on this forum early on (approximately 2008 or 2009) who stated this view also.

https://thearchdruidreport-archive.2006 ... fairy.htmlThe historian Arnold Toynbee, whose study of the rise and fall of civilizations is the most detailed and cogent for our purpose, has traced a recurring rhythm in this process. Falling civilizations oscillate between periods of intense crisis and periods of relative calm, each such period lasting anywhere from a few decades to a century or more—the pace is set by the speed of the underlying decline, which varies somewhat from case to case. Most civilizations, he found, go through three and a half cycles of crisis and stabilization—the half being, of course, the final crisis from which there is no recovery.

That’s basically the model that I’m applying to our future. One wrinkle many people miss is that we’re not waiting for the first of the three and a half rounds of crisis and recovery to hit; we’re waiting for the second. The first began in 1914 and ended around 1954, driven by the downfall of the British Empire and the collapse of European domination of the globe. During the forty years between Sarajevo and Dien Bien Phu, the industrial world was hammered by the First World War, the Spanish Flu pandemic, the Great Depression, millions of political murders by the Nazi and Soviet governments, the Second World War, and the overthrow of European colonial empires around the planet.

That was the first era of crisis in the decline and fall of industrial civilization. The period from 1945 to the present was the first interval of stability and recovery, made more prosperous and expansive than most examples of the species by the breakneck exploitation of petroleum and other fossil fuels, and a corresponding boom in technology. At this point, as fossil fuel reserves deplete, the planet’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide and other pollutants runs up against hard limits, and a galaxy of other measures of impending crisis move toward the red line, it’s likely that the next round of crisis is not far off.

What will actually trigger that next round, though, is anyone’s guess. In the years leading up to 1914, plenty of people sensed that an explosion was coming, some guessed that a general European war would set it off, but nobody knew that the trigger would be the assassination of an Austrian archduke on the streets of Sarajevo. The Russian Revolution, the March on Rome, the crash of ‘29, Stalin, Hitler, Pearl Harbor, Auschwitz, Hiroshima? No one saw those coming, and only a few people even guessed that something resembling one or another of these things might be in the offing.

Thus trying to foresee the future of industrial society in detail is an impossible task. Sketching out the sort of future that we could get is considerably less challenging. History has plenty to say about the things that happen when a civilization begins its long descent into chaos and barbarism, and it’s not too difficult to generalize from that evidence.

Higgenbotham wrote: Sat Dec 03, 2011 4:45 pmLooking at the scale of the raw numbers, the 1918 pandemic killed roughly 3% of the world population and WWII killed roughly 3% also. The bloody dictators in Europe and Asia killed a similar sized percentage of world population. This all happened over about a 50 year period. Despite this, world population continued to increase - there was no permanent reduction in population as occurred during the 14th Century.John wrote:Dear Higgie,

But I would have to question whether the 20th century was any less of

a "Dark Age" than the 14th century, especially if you're focused on

Europe. The two world wars were focused on Europe. These wars were

incredibly bloody and destructive, and if you extend to the end of the

century, you have the the bloody wars in eastern Europe (the old

Yugoslavia). And the Holocaust might (arguably) be considered worse

than the Hundred Years War.

There was even something comparable to the Black Death - namely, the

worldwide Spanish Flu epidemic in 1918.

So what can we conclude about the next decade? There will certainly

be an extremely bloody war, and I've estimated that it will kill some

2 billion people. But I have no reason to conclude that this war will

be any worse than WW I+II.

The raw figures bring up an interesting observation, though. The more permanent population reduction in 14th Century Europe (defining 14th Century Europe as a region relatively or completely unconnected from Asia and the Americas) was approximately 10 times the temporary world population reductions in the 20th Century.

A permanent reduction in population over some time scale longer than, say, a saeculum seems to be characteristic of a Dark Age as opposed to a normal crisis period. Naturally, this is a case of arbitrarily defining something as opposed to something else and giving it a name.

So how could a scale of population reduction that is 10 times that of the prior saeculum occur? My thesis is that a Dark Age scale population reduction can only come about through large scale individual moral and institutional failure. This is harder to quantify, but my previous post describes what that looks like as opposed to typical crisis period failure.

While the periphery breaks down rather slowly at first, the capital cities of the hegemon should collapse suddenly and violently.

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 3 guests