A Reporter at Large

The Tower Builder

By John Seabrook

November 11, 2001

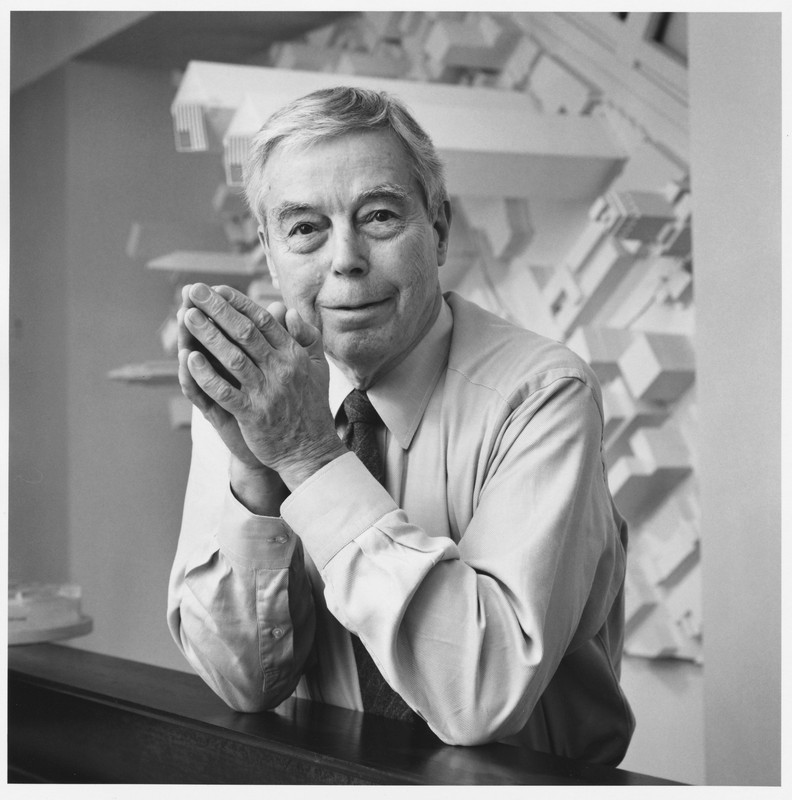

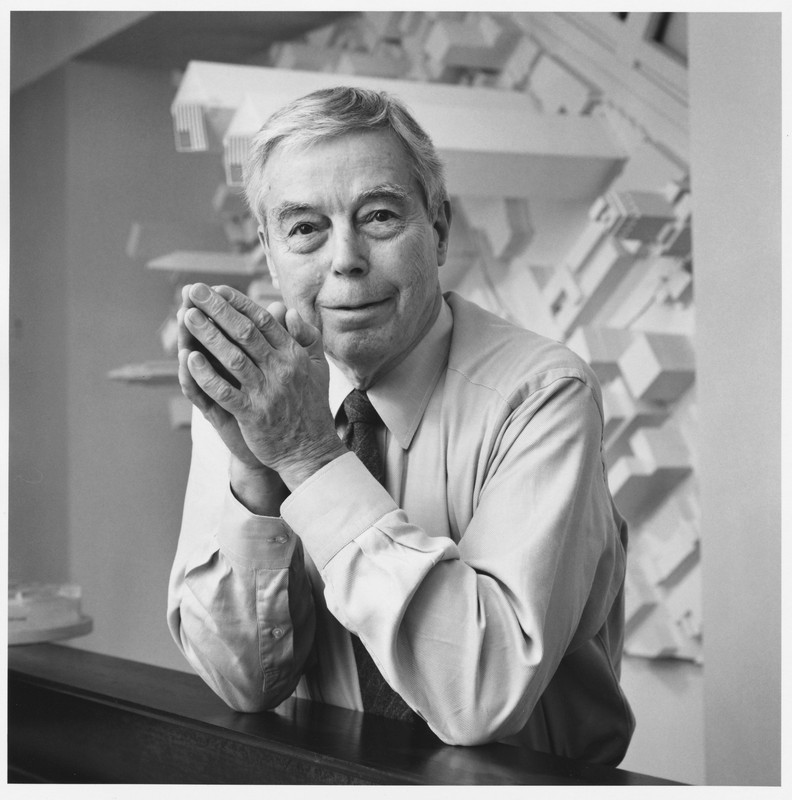

“I have a lot of tough nights,” Leslie E. Robertson, who helped design the World Trader Center, said.

Photograph by Alen MacWeeney

Structural engineers make buildings stand up, but the public doesn’t pay much attention to what they do until a building falls down. Although the safety of a building’s occupants depends on its structure, most people notice only the aesthetics, the furnishings, and the view, and give the architects, not the engineers, all the credit (or blame) for the results. Very few inhabitants of modern high-rises know where the load-bearing columns are placed, and how they are supported, or whether the building is a frame structure or a tube structure, and almost no one checks above the ceiling tiles to see how the floor overhead is attached to the vertical supports—all decisions that are worked out by the building’s structural engineers. The anonymity of the high-rise structural engineer is the reward for his genius. Part of the awe that skyscrapers command lies in their apparent freedom from gravity: they’re not just tall; they’re effortlessly tall.

Since the collapse of the World Trade Center towers, on September 11th, structural engineers and their profession have received a great deal of public attention. University engineering departments around the country have been staging public forums in which the “mechanics of failure” are debated; there’s one at Columbia University this week. The American Society of Civil Engineers and fema (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) are funding a team of twenty-four civil and fire-safety engineers to investigate what parts of the Twin Towers’ structure failed first, and how much damage was caused by the impact and blast of the airplanes, and how much by the ensuing fires. Dr. W. Gene Corley, a structural engineer with Construction Technology Laboratories, in Skokie, Illinois, who led fema’s investigation into the collapse of the nine-story Murrah Building, in Oklahoma City in 1995, is the over-all director of fema’s inquiry into the World Trade towers. In addition to inspecting the site of the disaster, he told me, his team will review photographs and enhanced videos of the collapse, examine the debris, and use information from firemen, policemen, survivors, and other witnesses in an attempt to reconstruct the moment at which each structure failed.

Of course, you don’t need an engineer to tell you why the towers fell down: two Boeing 767s, travelling at hundreds of miles an hour, and carrying more than ten thousand gallons of jet fuel each (if you converted the energy in the Oklahoma City bomb into jet fuel, it would amount to only fifty-one gallons), crashed into the north and south buildings at 8:45 a.m. and 9:06 a.m., respectively, causing them to fall—the south tower at 9:59 a.m. and the north tower at ten-twenty-eight. Nor do we need a government panel to tell us that the best way to protect tall buildings is to keep airplanes out of them. Nevertheless, there is considerable debate among experts about precisely what order of events precipitated the collapse of each building, and whether the order was the same in both towers. Did the connections between the floors and the columns give way first or did the vertical supports that remained after the impact lose strength in the fire, and, if so, did the exterior columns or the core columns give way first? “That’s the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question,” said Ron Hamburger, a structural engineer with ABS Consulting, in Oakland, California, who is also on fema’s team, when I asked which of these scenarios he favored. Although there may never be another event like the attack on the towers, the disaster also highlights several potential weaknesses in the way that many modern high-rises are constructed—weaknesses that the designers of the tall buildings of the future may want to consider.

Leslie E. Robertson is the engineer who, with his then partner, John Skilling, was mainly responsible for the structure of the Twin Towers. Unlike most of his colleagues, who have been widely quoted and interviewed, he has remained largely out of the public eye since September 11th. His only public appearance was at a previously scheduled meeting of the National Council of Structural Engineers Associations, on October 5th, in New Hampshire, where, as the Wall Street Journal reported, on being asked by an engineer in the audience, “Is there anything you wish you had done differently in the design of the building?,” Robertson broke down and wept at the lectern. Guy Nordenson, a structural engineer in New York and a professor at Princeton, who, like many of his colleagues, regards Robertson with great respect, showed me a recent E-mail he had received from him. It was a response to a letter Nordenson had written to the Times, praising the towers’ structural design for keeping them standing as long as they did, and allowing some twenty-five thousand people to escape. “It’s very Les,” he said, referring to Robertson, and pointed at his computer screen. “Almost Shakespearean.” Robertson had written:

Your words do much to abate the fire that writhes inside

It is hard

But that I had done a bit more . . .

Had the towers stood up for just one minute longer . . .

It is hard.

On a brilliantly sunny fall morning in late October, I visited Robertson’s offices, on the top two floors of 30 Broad Street, a forty-eight-story building that stands a few blocks from Ground Zero. From the windows of the conference room where I waited for Robertson, there was a clear view down into the rubble where the south tower once stood. Fires were still burning inside the pit, and the smell, that sweet acrid odor of burning metal and decay, was noticeable in the room. Many of the firm’s sixty employees, including Saw-Teen See, Robertson’s wife, who is also a partner in the firm, stood by these windows and watched as the second plane flew in over Hudson River Park, banked, and disappeared inside the south tower. See remembers closing her eyes at that moment, and didn’t see the fireball come out the other side.

I turned away from the view and studied pictures of other buildings that Robertson’s firm had worked on over the years, which were displayed around the room, including the Bank of China Tower, in Hong Kong, a twelve-hundred-and-nine-foot structure engineered by Robertson for I. M. Pei. Pei’s characteristic triangular shapes had been seamlessly translated into gigantic diagonal braces on the sides of the building. Structural engineers commonly complain that architects don’t understand how to construct high-rise buildings, from either a structural or an economic perspective, leaving it to the engineers to wrestle with the problems posed by the architecture and to resolve them in a way that allows the potential contractor to submit a bid for the project that is within the developer’s budget. Such a perfect marriage of architecture and structure as the Bank of China Tower is unusual in the creation of skyscrapers, but it is a distinguishing feature of many of the buildings that Robertson has worked on over the years, and especially the World Trade towers.

On entering the room, Robertson walked over and looked out the window at the smoking pile where his structures had once been. He seemed to do this casually, but as we stood there I noticed that he was trembling slightly. He remained before the window for almost a minute, with the air of a man forcing himself to confront something he didn’t want to confront, nodding as though to say, O.K., this is reality, I know it—but looking bewildered at the same time. When we sat down, he said, “The World Trade Center was a team effort, but the collapse of the World Trade Center is my responsibility, and that’s the way I feel about it.”

Robertson, who is seventy-three, wore a gray silk shirt that was open at the collar. His hair is mostly white, and longish, falling over his ears, and with bangs in front, which gives him a slightly bohemian look. His brown eyes are like very deep pools, and the flesh below the eyes was swollen, either with fatigue or with grief. As we talked, he frequently looked out the window. I felt the absence of the buildings in him. “That’s how people introduced me,” he said. “I was the designer of the World Trade Center. Although that was wrong, actually—I only assisted on the team that designed it. But that’s who I was.”

Robertson was in Hong Kong on September 11th, having dinner with the developers of a skyscraper that will be built in Kowloon. “A woman’s cell phone rang, and she said an airplane had hit the World Trade towers. I thought it was an accident, one of the helicopters that were always flying overhead. A short time later, my wife called me and said the second plane had hit, and I went upstairs and turned on the television. I knew both buildings were hit by planes, both on fire. I had no idea whether there were a thousand people or fifty thousand people at risk. I knew the fire was burning out of control, I knew people were jumping to get away from the heat . . .” His eyes searched the empty view again.

“Before the buildings collapsed,” I asked, “did any part of your brain, calculating, say, ‘There’s probably this amount of jet fuel, this amount of fire protection—the building has this long to last’?”

“I can’t . . . I think there are times when logic just isn’t the right way to think.” Robertson’s eyes were filling with tears. “This all took place in an hour and a half. The TV was on. I don’t know if what I saw was the buildings falling down on rerun or whether it was live. I was just focussed on getting back to New York City. I remember packing my bags. And when the building collapsed—it was totally devastating.”